It's been eight months since we made the trek through the cold to reenact our fathers' footsteps as they were force-marched 60+ miles from Stalag Luft III to Spremberg, Germany, during the bitterly cold winter of 1945. I'm wondering what my new-found friends are doing now - how did the trip impact their lives and what they have pursued since? I know that I, for one, am well aware of the brevity of time I have left with my father, who is now 91 years old. He has published his memoirs and I greatly value the time we spent together gathering the illustrations for the book. I'm more aware, too, of the current conflicts we're involved in as a nation, and am more grateful for the sacrifices that have been, and are being made to protect our precious liberties. I also have a better appreciation for what my father went through so many years ago and why he cares so deeply about the things that are important to him.

Where are my Kriegie Kid friends now, and how are they feeling about our challenging and emotional experience? I'm encouraging them to post a reflective comment on how the trip has impacted their lives and their thinking about what their fathers (and Val's uncle and George's friends) endured ...

Read more!

Tuesday, October 06, 2009

Saturday, June 27, 2009

Lest They Forget Freedom's Price

Ed Bender's account of his time as a B-17 bomber pilot and POW at Stalag Luft III has been published as the book, "Lest They Forget Freedom's Price: Memoirs of a WWII Bomber Pilot." It is available at:

AuthorHouse

It is also available via Amazon.com and barnesandnoble.com

STAY TUNED FOR A LISTING OF OTHER BOOKS & RESOURCES RECOMMENDED BY THE KRIEGIE KIDS! Read more!

Wednesday, April 08, 2009

Aliceville POW Museum Presentation

Former Stalag Luft III POW Lt. Col. Edward M. Bender (USAFR, retired) and his daughter, Miriam, recently presented two items they presented to the Aliceville POW Museum in Alabama last March. These items were donated by Hans Burkhardt, a resident of Spremberg, Germany, who had received them from his friend, Ervin Vorssatz. Vorssatz was a German prisoner of war held in Arkansas during World War II. He had carved the eagle head while there and had saved his POW wages to buy the pocket watch. To view pictures and to read more about the Aliceville POW Museum, use the "Read More" link below.

Former Stalag Luft III POW Lt. Col. Edward M. Bender (USAFR, retired) and his daughter, Miriam, recently presented two items they presented to the Aliceville POW Museum in Alabama last March. These items were donated by Hans Burkhardt, a resident of Spremberg, Germany, who had received them from his friend, Ervin Vorssatz. Vorssatz was a German prisoner of war held in Arkansas during World War II. He had carved the eagle head while there and had saved his POW wages to buy the pocket watch. To view pictures and to read more about the Aliceville POW Museum, use the "Read More" link below.Here is the contact information for the museum at Aliceville, AL:

Aliceville POW Museum & Cultural Center

Mary Bess Paluzzi, Director

Aliceville POW Museum & Cultural Center

104 Broad Street

Aliceville, AL 35442

205-373-2365

museum@nctv.com

Friday, March 27, 2009

Annotated Bibliography of POW Memoirs, WWII, Europe and North Africa

Those interested in books on the POW experience from WWII should check out Tamara Haygood's annotated bibliography at http://wlajournal.com/moab

Tamara, Lindsay Liles, and William Newmiller have compiled a searchable database that provides author, bibliographic information, nationality of the memoir writer, language, affilitation, date captured, camps, the percent of the memoirs that deal with the POW experience, and a rating. Read more!

Tamara, Lindsay Liles, and William Newmiller have compiled a searchable database that provides author, bibliographic information, nationality of the memoir writer, language, affilitation, date captured, camps, the percent of the memoirs that deal with the POW experience, and a rating. Read more!

Wednesday, March 25, 2009

Honor Roll of SLIII POWs

Take a moment to click on the link and view the Stalag Luft III former POWs that we are honoring on this site.

If you personally know an SLIII former-POW that you would like to have honored on the site, send their name, rank, the compound and (if known) the barracks they were in to: larsonsintn@comcast.net In addition, if you have a picture that you can scan and send, we will post it as well.

Link to the names and pictures of former SLIII POWs

If the former SLIII POW you are honoring is still living and he would like to contact other living SLIII POWs or would like to attend the next SLIII Reunion, please post a comment on this post. Read more!

If you personally know an SLIII former-POW that you would like to have honored on the site, send their name, rank, the compound and (if known) the barracks they were in to: larsonsintn@comcast.net In addition, if you have a picture that you can scan and send, we will post it as well.

Link to the names and pictures of former SLIII POWs

If the former SLIII POW you are honoring is still living and he would like to contact other living SLIII POWs or would like to attend the next SLIII Reunion, please post a comment on this post. Read more!

Monday, March 09, 2009

Pieces of History

As noted in a previous post below, we were blessed to meet Hans Burkhardt at the Spremberg Hotel, and he showed us the train station where our fathers were loaded onto boxcars for the trip to camps at Nuremberg and Moosburg. Hans had an older friend who fought in the war and was captured by the Allies. That friend, Ervin Vorssatz, was shipped to America and spent time in a POW camp in Arkansas. There he worked and made handcrafted items while in the prison camp, bringing home a pocketwatch purchased with his POW wages, and a wooden plaque that he carved of an eagle's head (there were eagles that nested by the river near the camp where he was held). This month, I will take my father, Edward Bender, to the POW museum at Aliceville, Alabama to donate these items.

To see information on the POW museum in Aliceville, Alabama, click the "Read More" link.

Here is the contact information for the museum at Aliceville, AL:

Aliceville POW Museum & Cultural Center

Ann Kirksey, Director

Aliceville POW Museum & Cultural Center

104 Broad Street

Aliceville, AL 35442

205-373-2365

museum@nctv.com

Read more!

Tuesday, March 03, 2009

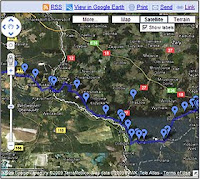

Road from Sagan - the revised interactive map.

Click here to follow the route 12,000 Allied POWs took when they were forced to evacuate the German prisoner of war camp, Stalag Luft III, on the night of January 27, 1945, into the teeth of a raging blizzard. In a line stretching nearly 20 miles long, they were marched west 52 miles to Spremberg, Germany, where they were then crammed on box cars and transported to Stalag VII in Bavaria.

Click here to go to an interactive map where you can follow along the route we Kriegie Kids took as we retraced the steps of our fathers. When the map fully loads, you may use the zoom in/out tool, and you can left click and drag the map underneath you - but first click on the double [<<] at the top center of the map to clear the symbols on the left which will widen the map view. The journey begins in Poland at the eastern end of the map, at the site of Stalag Luft III, and ends in the German city of Spremberg at the train yards. Along the route are various pins that you can click on which will reveal interesting information and pictures. When you encounter a place on the map that has a lot of pins, zoom in further and further to spread the pins out and to get a better view of the land underneath. If you zoom in too far the resolution will fail. Have fun!! For a list of some of the Polish towns and their German names that were used during the war, use the "Read More" link below:

Here is the list of some of the Polish towns and their German names used during the war:

Zagan - Sagan

Czerna - Hammerfeld

Ilowa - Halbau

Borowe - Charlottenhof

Godznica - Freiwaldau

Lipna - Selingersruh

Przewoz - Priebus

Potok - Pattag

Read more!

Click here to go to an interactive map where you can follow along the route we Kriegie Kids took as we retraced the steps of our fathers. When the map fully loads, you may use the zoom in/out tool, and you can left click and drag the map underneath you - but first click on the double [<<] at the top center of the map to clear the symbols on the left which will widen the map view. The journey begins in Poland at the eastern end of the map, at the site of Stalag Luft III, and ends in the German city of Spremberg at the train yards. Along the route are various pins that you can click on which will reveal interesting information and pictures. When you encounter a place on the map that has a lot of pins, zoom in further and further to spread the pins out and to get a better view of the land underneath. If you zoom in too far the resolution will fail. Have fun!! For a list of some of the Polish towns and their German names that were used during the war, use the "Read More" link below:

Here is the list of some of the Polish towns and their German names used during the war:

Zagan - Sagan

Czerna - Hammerfeld

Ilowa - Halbau

Borowe - Charlottenhof

Godznica - Freiwaldau

Lipna - Selingersruh

Przewoz - Priebus

Potok - Pattag

Read more!

Thursday, February 26, 2009

Diary of Kriegie Kids March

It is 1:00 a.m. We have been walking for almost 2 hours. It is cold, dark, and dogs bark at us as we pass through villages. As we struggle to finish our first night’s walk, I ask myself, how did we get ourselves into this?

My husband Kirk and I meet Val Burgess at the Stalag Luft III P.O.W. Reunion in 2007. Val has been involved in setting up the reunions, and also taking oral histories of the men who were incarcerated there. She mentions that she would like to recreate the forced march that the men in Stalag Luft III did in January of 1945. The Russians were advancing, and Hitler orders that all allied airmen will be moved to one camp near Munich, Stalag 7A. So the men march out in a miserable snowstorm on January 27, 1945. There are 10,000 men all told, and they struggle to march 100 kilometers on few pieces of bread and water. At Spremberg, they are loaded into boxcars and after three horrific days, they reach Stalag Luft 7A, where they remain until they are liberated in April of 1945.

A flurry of emails are sent out to see who is interested. We find 15 children of those P.O.W.s who are committed to doing this trip. It is decided. We will do this march in January of 2009. We will follow the footsteps of South Camp, in which my father James Gore was incarcerated from July of 1943 to January of 1945. Although this march is regularly reenacted by the British, we will be the first Americans to actually walk the whole distance.

To read the diary of our trip, use the "Read More" link...

January 25, 2009 – Our group meets in Berlin. We are from Ohio, Wyoming, Illinois, Michigan, Kansas, Washington, Tennesee, Missouri, Arizona, and Colorado. We discover that our group has a great sense of humor, and are ready for anything. We range from 40 to 63 in age. After a day of sightseeing together, we have our first meal, with everyone ready to try traditional German food. Exactly what part of the pig is pork knuckle?

January 26 - We meet our bus driver for breakfast. Oops, he speaks no English! Luckily one of our group speaks some German, and with a German phrase book, we are in business. We head for Zagan Poland, which is the location of Stalag Luft III. Jacek, the museum curator, is waiting for us. He takes us through the museum, and then we are outside, climbing into a replica of tunnel Harry of the movie Great Escape fame. There is also a replica of a guard tower, and we climb up to check out the view. The RAF has just completed a replica of Hut 104, which was the number of the hut from which tunnel Harry started, and it is exciting to see just how the barracks were set up. Then we proceed to the various camps of Stalag Luft III

The weather is cloudy and cold. The ground is frozen, with about 3 inches of snow. It is slippery and slow going, but Jacek is able to locate the barracks that housed each of our dads. Having been to Stalag Luft III in 2005 with my 88-year old dad, I know this will be an emotional experience, and it is. We conclude the day with dark falling at the monument to the fifty British who were shot after escaping from tunnel Harry.

January 27 – We finish visiting the location of the camps, including Belaria, across town. Jacek also takes us to the grainery where Red Cross packages were delivered, and to the train tunnel that our fathers walked through to start their stay at the camp. We then drive to Halbau, or Ilowa as it is now called, and leave our luggage. Ilowa is our goal for walking this night. We return to Zagan by bus, and after dinner, we are ready to get started..

We follow Jacek through the woods in the dark to reach South Camp. Part of our group gets lost, and we must go back for them, but the walkie talkies that we are carrying help. Together at last at the South camp site, we say a prayer for our fathers and to the success of our march, and off we go! It is around 11:00 p.m. January 27, the same time South camp started 64 years ago. We are quite a site, each of us with a reflective vest and head lamp. We quickly spread out on the road. Faster walkers move ahead, medium walkers in the middle, and slower walkers are directly in front of the bus. We talk about our dads, and the storm they walked through in 1945. My dad described it as snowing horizontally. In 2009, it is not snowing, nor is there snow on the road.

We cross the overpass, where in 1945, our fathers looked back to see Stalag Luft III burning. We reach our hotel, and are finished for the night. We have walked 9.7 miles, and it is around 2:30 a.m. Everyone is in good spirits.

January 28 – Jacek meets us and takes us to a school in Ilowa. The RAF supports this school, and there are pictures of the march of 1945 inside, as well as plaques in honor of those men. The children give us a tour of their school. They are excited, because although the RAF regularly visits the school on their march reenactment, we are the first Americans to visit. Jacek takes us to the church next door. Although South camp did not stay there, some of the other camps found shelter at this church.

It is time to resume our walk. Today is a tough day. We walk through the villages of Borowe, Gozdnica, and Przewoz. Some of our walk is on cobblestones, and some is on very busy roads, which are both difficult to negotiate. We finish well after dark, around 7 p.m. We have walked 18.7 miles. We have dinner, and with feet throbbing, go to bed. We are now starting to have blisters, sore backs and sore legs. Even in our agony, we know that it is nothing compared to our fathers’ experience.

January 29 –Jacek meets us once again and takes us to an area called Grosselten. This was the first place that South camp actually stopped to sleep for all of 4 hours. Here are the huge barns that my father talks about. They are still standing, but abandoned. It was an eery feeling to know we stand where South camp slept 64 years ago.

Again, we visit a local school, and are provided with refreshments. When we start our walk today, it is much better. The road is not heavily traveled, and we spread out over a mile once again. The bus moves ahead of us today, and waits for us every few miles. We come to a fork in the road, and some of the people in front have to be retrieved because they have gone the wrong direction. We walk through the villages of Potok and Leknica. Today’s walk is 14.3 miles, again finishing after dark, around 5:30 p.m. South camp also reached Bad Muskau on the 29th, but at 2:00 a.m. after 27 grueling hours of walking.

January 30 – Jacek meets us to show us one of the tile factories that South camp rested in for 2 days before continuing to Spremberg. The factories had cement floors, but were a warm and welcome rest in 1945. Even though the factory looks different today, we are invited to go inside and see a painting of how it looked in 1945.

Jacek says goodbye to us at the factory. He has made our trip much more meaningful, and will post our information on his website.

Today is our last day of walking. We follow the footsteps of South camp through Kromlau and Graustein. Part of our day is on a very busy highway, with cars and trucks roaring past us. What was it like in 1945? But we eventually find a bicycle path next to the highway and walking becomes easier. Again, we end our walk in the dark having completed 17.5 miles. We have made it to Spremberg! All told, our walk adds up to 60.2 miles, around 100 kilometers. We have recreated the march our fathers did, and felt a small part of their agony, knowing all the while they didn’t have warm meals and a hotel waiting for them every night.

January 31 – In Spremberg , South camp was loaded onto 40 and 8 box cars, and spent 3 horrific days traveling to their final destination in Moosberg, Stalag 7A. We visit the train station, and meet a man who was a boy in 1945. He remembers seeing thousands of American POWs being loaded onto boxcars, and felt sorry for them, as they were cold, hungry and had no gloves. We continue, on the bus now, to Dresden for a quick visit, then on to Nurnberg.

February 1 - It is Sunday, and some of our group go to their respective churches. Others go to ex-Nazi sights, such as the famous Hitler parade grounds and the Documentation center, explaining the rise of Hitler to power.

February 2 – Some of the compounds were sent to Nurnberg before they continued to Moosberg. We were able to locate the site of this camp, although there is nothing left there.

We continue to Moosberg, Stalag 7A. Our fathers arrived at different times, but eventually were all there. The camp was built for 40,000 men, but housed 150,000 by April of 1945. Overcrowding caused horrific conditions, sickness, dysentery, and not enough food. My father lost 50 pounds in the 3 months he was there. However, the men were treated to the amazing sight of American tanks crashing through the gates on April 29, 1945. They were free!

We met with Bernhard Kerscher, the museum curator. Kerscher spoke only German, but had an interpreter with him. The museum had a lot of pictures of the conditions of Stalag 7A, as well as a model of the camp. Bernhard takes us to one of the few barracks that is left. The camp site is now low income housing. He is also able to take us to a cemetery that held mass graves for men who died in Stalag 7A, including 11 Americans.

Munich is our stop for the night. We are quiet on the bus, thinking about our experiences together. As some of the group have flights to catch in the morning, we say goodbye at dinner. We have had a unique experience, not knowing each other at all, but coming together in the common bond of honoring our fathers. We will have wonderful memories of the trek that took us from Zagan to Moosberg, and beyond!

My husband Kirk and I meet Val Burgess at the Stalag Luft III P.O.W. Reunion in 2007. Val has been involved in setting up the reunions, and also taking oral histories of the men who were incarcerated there. She mentions that she would like to recreate the forced march that the men in Stalag Luft III did in January of 1945. The Russians were advancing, and Hitler orders that all allied airmen will be moved to one camp near Munich, Stalag 7A. So the men march out in a miserable snowstorm on January 27, 1945. There are 10,000 men all told, and they struggle to march 100 kilometers on few pieces of bread and water. At Spremberg, they are loaded into boxcars and after three horrific days, they reach Stalag Luft 7A, where they remain until they are liberated in April of 1945.

A flurry of emails are sent out to see who is interested. We find 15 children of those P.O.W.s who are committed to doing this trip. It is decided. We will do this march in January of 2009. We will follow the footsteps of South Camp, in which my father James Gore was incarcerated from July of 1943 to January of 1945. Although this march is regularly reenacted by the British, we will be the first Americans to actually walk the whole distance.

To read the diary of our trip, use the "Read More" link...

January 25, 2009 – Our group meets in Berlin. We are from Ohio, Wyoming, Illinois, Michigan, Kansas, Washington, Tennesee, Missouri, Arizona, and Colorado. We discover that our group has a great sense of humor, and are ready for anything. We range from 40 to 63 in age. After a day of sightseeing together, we have our first meal, with everyone ready to try traditional German food. Exactly what part of the pig is pork knuckle?

January 26 - We meet our bus driver for breakfast. Oops, he speaks no English! Luckily one of our group speaks some German, and with a German phrase book, we are in business. We head for Zagan Poland, which is the location of Stalag Luft III. Jacek, the museum curator, is waiting for us. He takes us through the museum, and then we are outside, climbing into a replica of tunnel Harry of the movie Great Escape fame. There is also a replica of a guard tower, and we climb up to check out the view. The RAF has just completed a replica of Hut 104, which was the number of the hut from which tunnel Harry started, and it is exciting to see just how the barracks were set up. Then we proceed to the various camps of Stalag Luft III

The weather is cloudy and cold. The ground is frozen, with about 3 inches of snow. It is slippery and slow going, but Jacek is able to locate the barracks that housed each of our dads. Having been to Stalag Luft III in 2005 with my 88-year old dad, I know this will be an emotional experience, and it is. We conclude the day with dark falling at the monument to the fifty British who were shot after escaping from tunnel Harry.

January 27 – We finish visiting the location of the camps, including Belaria, across town. Jacek also takes us to the grainery where Red Cross packages were delivered, and to the train tunnel that our fathers walked through to start their stay at the camp. We then drive to Halbau, or Ilowa as it is now called, and leave our luggage. Ilowa is our goal for walking this night. We return to Zagan by bus, and after dinner, we are ready to get started..

We follow Jacek through the woods in the dark to reach South Camp. Part of our group gets lost, and we must go back for them, but the walkie talkies that we are carrying help. Together at last at the South camp site, we say a prayer for our fathers and to the success of our march, and off we go! It is around 11:00 p.m. January 27, the same time South camp started 64 years ago. We are quite a site, each of us with a reflective vest and head lamp. We quickly spread out on the road. Faster walkers move ahead, medium walkers in the middle, and slower walkers are directly in front of the bus. We talk about our dads, and the storm they walked through in 1945. My dad described it as snowing horizontally. In 2009, it is not snowing, nor is there snow on the road.

We cross the overpass, where in 1945, our fathers looked back to see Stalag Luft III burning. We reach our hotel, and are finished for the night. We have walked 9.7 miles, and it is around 2:30 a.m. Everyone is in good spirits.

January 28 – Jacek meets us and takes us to a school in Ilowa. The RAF supports this school, and there are pictures of the march of 1945 inside, as well as plaques in honor of those men. The children give us a tour of their school. They are excited, because although the RAF regularly visits the school on their march reenactment, we are the first Americans to visit. Jacek takes us to the church next door. Although South camp did not stay there, some of the other camps found shelter at this church.

It is time to resume our walk. Today is a tough day. We walk through the villages of Borowe, Gozdnica, and Przewoz. Some of our walk is on cobblestones, and some is on very busy roads, which are both difficult to negotiate. We finish well after dark, around 7 p.m. We have walked 18.7 miles. We have dinner, and with feet throbbing, go to bed. We are now starting to have blisters, sore backs and sore legs. Even in our agony, we know that it is nothing compared to our fathers’ experience.

January 29 –Jacek meets us once again and takes us to an area called Grosselten. This was the first place that South camp actually stopped to sleep for all of 4 hours. Here are the huge barns that my father talks about. They are still standing, but abandoned. It was an eery feeling to know we stand where South camp slept 64 years ago.

Again, we visit a local school, and are provided with refreshments. When we start our walk today, it is much better. The road is not heavily traveled, and we spread out over a mile once again. The bus moves ahead of us today, and waits for us every few miles. We come to a fork in the road, and some of the people in front have to be retrieved because they have gone the wrong direction. We walk through the villages of Potok and Leknica. Today’s walk is 14.3 miles, again finishing after dark, around 5:30 p.m. South camp also reached Bad Muskau on the 29th, but at 2:00 a.m. after 27 grueling hours of walking.

January 30 – Jacek meets us to show us one of the tile factories that South camp rested in for 2 days before continuing to Spremberg. The factories had cement floors, but were a warm and welcome rest in 1945. Even though the factory looks different today, we are invited to go inside and see a painting of how it looked in 1945.

Jacek says goodbye to us at the factory. He has made our trip much more meaningful, and will post our information on his website.

Today is our last day of walking. We follow the footsteps of South camp through Kromlau and Graustein. Part of our day is on a very busy highway, with cars and trucks roaring past us. What was it like in 1945? But we eventually find a bicycle path next to the highway and walking becomes easier. Again, we end our walk in the dark having completed 17.5 miles. We have made it to Spremberg! All told, our walk adds up to 60.2 miles, around 100 kilometers. We have recreated the march our fathers did, and felt a small part of their agony, knowing all the while they didn’t have warm meals and a hotel waiting for them every night.

January 31 – In Spremberg , South camp was loaded onto 40 and 8 box cars, and spent 3 horrific days traveling to their final destination in Moosberg, Stalag 7A. We visit the train station, and meet a man who was a boy in 1945. He remembers seeing thousands of American POWs being loaded onto boxcars, and felt sorry for them, as they were cold, hungry and had no gloves. We continue, on the bus now, to Dresden for a quick visit, then on to Nurnberg.

February 1 - It is Sunday, and some of our group go to their respective churches. Others go to ex-Nazi sights, such as the famous Hitler parade grounds and the Documentation center, explaining the rise of Hitler to power.

February 2 – Some of the compounds were sent to Nurnberg before they continued to Moosberg. We were able to locate the site of this camp, although there is nothing left there.

We continue to Moosberg, Stalag 7A. Our fathers arrived at different times, but eventually were all there. The camp was built for 40,000 men, but housed 150,000 by April of 1945. Overcrowding caused horrific conditions, sickness, dysentery, and not enough food. My father lost 50 pounds in the 3 months he was there. However, the men were treated to the amazing sight of American tanks crashing through the gates on April 29, 1945. They were free!

We met with Bernhard Kerscher, the museum curator. Kerscher spoke only German, but had an interpreter with him. The museum had a lot of pictures of the conditions of Stalag 7A, as well as a model of the camp. Bernhard takes us to one of the few barracks that is left. The camp site is now low income housing. He is also able to take us to a cemetery that held mass graves for men who died in Stalag 7A, including 11 Americans.

Munich is our stop for the night. We are quiet on the bus, thinking about our experiences together. As some of the group have flights to catch in the morning, we say goodbye at dinner. We have had a unique experience, not knowing each other at all, but coming together in the common bond of honoring our fathers. We will have wonderful memories of the trek that took us from Zagan to Moosberg, and beyond!

Read more!

Article written by Pine River Times prior to our trip

In her father’s footsteps: Bayfield couple joins group enacting march from POW camp

By Melanie Brubaker Mazur

Times editor

By Melanie Brubaker Mazur

Times editor

If we whine about car problems or a slow economy or defiant children, we might want to consider the plight of Jim Gore.

At the end of World War II, the boy from Oxford, Colo. had been in a Nazi prisonor of war camp for nearly two years. As the Allied forces were advancing on the Nazis, the Germans started moving their POWs away from the front, jamming them into smaller camps.

Gore and his fellow POWs started their forced march at 11 p.m., on Jan. 27, 1945, marching 52 miles in the bitter winter cold, then they had a three-day train ride to Stalag VIIA in Moosburg, Germany.

This week, Gore’s daughter and son-in-law, Evelyn and Kirk McLaughlin of Bayfield, are joining 14 other children of the prisoners of war in recreating that forced march of 52 miles. Gore was 27 at the time. Now he’s 92.

To read the rest of the article, use the "Read More" link...

The McLaughlins left yesterday on their trip, starting in Poland. The trip concludes Feb. 3. Jim Gore was in Stalag Luft III in Sagan, Germany, now in Poland, which was the basis for the movie, “The Great Escape.”

“I’m twice his age,” Evelyn McLaughlin said of her father’s forced march in 1945. “But I have better gear.”

McLaughlin started attending POW conventions with her father, which is where some of the children started toying with the idea of enacting their fathers’ march. Of the men they are honoring, three are still alive, including Gore.

“I’m just thrilled to pieces,” Gore said of his daughter’s decision to walk during the cold Polish winter. “What they’re doing is just remarkable. I’m grateful and proud.”

McLaughlin and her mother, Dorothy, joined Jim in a trip to Poland and Germany in 2005 to visit the camps where he was held. Then they started thinking about that freezing cold march, in skimpy uniforms and bad-fitting shoes.

“It’s not about us,” McLaughlin said this week before she left. “It’s honoring them and trying to keep their memory of what they did alive.”

The prisoners called themselves “kriegies,” playing on the German word for war, “krieg.” Several “kriegies” wanted to come along, but their age and ill health didn’t make it possible.

The 16 walkers range in age from 40 to 63. They’ve been profiled in a POW magazine and have received several calls and messages from World War II veterans wishing them luck. They know they’ll have it a lot easier than their dads. They’re walking 10 to 15 miles a day, staying in small inns along the way, and a bus is following and taking their gear.

While they have 16 people, McLaughlin said the Stalag camps were huge – her father’s had 10,000 men.

He had been in Stalag Luft III for a year and a half when they received orders to march on the cold January night. Ironically, they had been watching a production of “You Can’t Take it With You” when they received orders to march. Although Stalag III was a POW camp, it did have activities and the men were fed and clothed. Gore has told his daughter repeatedly that he knew he was one of the lucky ones.

A navigator on a B-17, Gore was shot down on his fifth mission over Germany, a bombing run on Hamburg. He was lucky he survived – the plane exploded, and he was blown out of the plane. He doesn’t remember pulling his parachute cord, but it opened, he swung once in the air, then hit the ground. He was picked up by German troops near Osnabruck, then taken to Stalag III.

During the forced march, they walked 35 miles in the first 27 hours, with little food and one four-hour stop in barns and stables. The first 2,000 men formed a column a mile long, tramping down the snow for the 8,000 men who followed behind. Eventually, the line of prisoners would stretch 20 miles. Gore’s group finally stopped and slept in a glass factory in Muskau for two days. Although they were sleeping on a concrete floor, the factory was heated, a relief for the exhausted prisoners. Hitler’s orders to march the POWs violated the Geneva Convention, which stated prisoners could not be marched more than 12.6 miles in 24 hours. That winter in Silesia, the region of Germany and Poland where they marched, was the coldest on record in 50 years.

McLaughlin said her father told her once that he fell over in the snow and didn’t want to go on.

“His roommate kicked him until he got up,” she said.

Gore said he still remembers the march vividly, and periodically talks about it with local high school students.

“The snowflakes were horizontal,” he said.

The McLaughlins started training seriously for the walk this summer, typically walking five miles three times a week. They walked the whole 53 miles in four days in December. Evelyn McLaughlin said she often walked with her friend, Debbie Janus. “She really stuck there with me,” she said.

Eventually, Gore was in a camp with 150,000 men that was designed to hold 40,000. He lost 50 pounds because there wasn’t enough to eat.

Finally liberated later that year, Jim Gore returned home and married his childhood sweetheart, Dorothy. They both taught for years in Durango schools. Evelyn said she always remembers her dad as a gentle man, but that he had the strength to make that march 64 years ago still amazes her.

Read more!

At the end of World War II, the boy from Oxford, Colo. had been in a Nazi prisonor of war camp for nearly two years. As the Allied forces were advancing on the Nazis, the Germans started moving their POWs away from the front, jamming them into smaller camps.

Gore and his fellow POWs started their forced march at 11 p.m., on Jan. 27, 1945, marching 52 miles in the bitter winter cold, then they had a three-day train ride to Stalag VIIA in Moosburg, Germany.

This week, Gore’s daughter and son-in-law, Evelyn and Kirk McLaughlin of Bayfield, are joining 14 other children of the prisoners of war in recreating that forced march of 52 miles. Gore was 27 at the time. Now he’s 92.

To read the rest of the article, use the "Read More" link...

The McLaughlins left yesterday on their trip, starting in Poland. The trip concludes Feb. 3. Jim Gore was in Stalag Luft III in Sagan, Germany, now in Poland, which was the basis for the movie, “The Great Escape.”

“I’m twice his age,” Evelyn McLaughlin said of her father’s forced march in 1945. “But I have better gear.”

McLaughlin started attending POW conventions with her father, which is where some of the children started toying with the idea of enacting their fathers’ march. Of the men they are honoring, three are still alive, including Gore.

“I’m just thrilled to pieces,” Gore said of his daughter’s decision to walk during the cold Polish winter. “What they’re doing is just remarkable. I’m grateful and proud.”

McLaughlin and her mother, Dorothy, joined Jim in a trip to Poland and Germany in 2005 to visit the camps where he was held. Then they started thinking about that freezing cold march, in skimpy uniforms and bad-fitting shoes.

“It’s not about us,” McLaughlin said this week before she left. “It’s honoring them and trying to keep their memory of what they did alive.”

The prisoners called themselves “kriegies,” playing on the German word for war, “krieg.” Several “kriegies” wanted to come along, but their age and ill health didn’t make it possible.

The 16 walkers range in age from 40 to 63. They’ve been profiled in a POW magazine and have received several calls and messages from World War II veterans wishing them luck. They know they’ll have it a lot easier than their dads. They’re walking 10 to 15 miles a day, staying in small inns along the way, and a bus is following and taking their gear.

While they have 16 people, McLaughlin said the Stalag camps were huge – her father’s had 10,000 men.

He had been in Stalag Luft III for a year and a half when they received orders to march on the cold January night. Ironically, they had been watching a production of “You Can’t Take it With You” when they received orders to march. Although Stalag III was a POW camp, it did have activities and the men were fed and clothed. Gore has told his daughter repeatedly that he knew he was one of the lucky ones.

A navigator on a B-17, Gore was shot down on his fifth mission over Germany, a bombing run on Hamburg. He was lucky he survived – the plane exploded, and he was blown out of the plane. He doesn’t remember pulling his parachute cord, but it opened, he swung once in the air, then hit the ground. He was picked up by German troops near Osnabruck, then taken to Stalag III.

During the forced march, they walked 35 miles in the first 27 hours, with little food and one four-hour stop in barns and stables. The first 2,000 men formed a column a mile long, tramping down the snow for the 8,000 men who followed behind. Eventually, the line of prisoners would stretch 20 miles. Gore’s group finally stopped and slept in a glass factory in Muskau for two days. Although they were sleeping on a concrete floor, the factory was heated, a relief for the exhausted prisoners. Hitler’s orders to march the POWs violated the Geneva Convention, which stated prisoners could not be marched more than 12.6 miles in 24 hours. That winter in Silesia, the region of Germany and Poland where they marched, was the coldest on record in 50 years.

McLaughlin said her father told her once that he fell over in the snow and didn’t want to go on.

“His roommate kicked him until he got up,” she said.

Gore said he still remembers the march vividly, and periodically talks about it with local high school students.

“The snowflakes were horizontal,” he said.

The McLaughlins started training seriously for the walk this summer, typically walking five miles three times a week. They walked the whole 53 miles in four days in December. Evelyn McLaughlin said she often walked with her friend, Debbie Janus. “She really stuck there with me,” she said.

Eventually, Gore was in a camp with 150,000 men that was designed to hold 40,000. He lost 50 pounds because there wasn’t enough to eat.

Finally liberated later that year, Jim Gore returned home and married his childhood sweetheart, Dorothy. They both taught for years in Durango schools. Evelyn said she always remembers her dad as a gentle man, but that he had the strength to make that march 64 years ago still amazes her.

Wednesday, February 18, 2009

Helpful Research Websites

I have compiled a list of what I found to be very useful websites that I have used for WWII and POW research. Click on the link to see them, and then you can save a pdf of the list of links by going to "file --> save as" in your browser window and entering where on your computer you would like it saved.

Click here for Marilyn's helpful research websites and information

Read more!

Click here for Marilyn's helpful research websites and information

Read more!

Monday, February 16, 2009

Prison Camps for Allied Prisoners of War in 1944

This is a map of the prison camps in 1944 (click for a larger picture). Marilyn also provided a listing of the camps (click read more to view it).

Here is the listing from Marilyn on the camps in 1944.

Read more!

Interview With The Southeast Missourian Prior to Our Trip

Rudi Keller, a staff reporter with The Southeast Missourian in Cape Girardeau, Missouri, posted an article and a short video of an interview he did with my dad, former Stalag Luft III POW Edward Bender, and my sister, Diane Maurer, prior to our trip to begin the "Road from Sagan".

Here is the link to the article

and

Here is the link to the video

If the article is no longer posted, here is the text of it:

Children of former World War II POWs re-enact their fathers' 1945 forced march

Saturday, January 17, 2009

By Rudi Keller

Southeast Missourian

[Pictured is a portion of the official German prisoner of war record registering Edward Bender after his capture in France in 1944. (ELIZABETH DODD ~ edodd@semissourian.com)]

At the beginning of 1945, the Soviet Red Army was massing more than 2 million men and 4,500 tanks in Poland for the offensive that would take them to the steps of the Reichstag in Berlin, the seat of German Nazi power.

The German Wehrmacht, thwarted in its winter offensive in the Ardennes Forest known as the Battle of the Bulge, was putting young boys and old men into fighting units. They were no match for the veteran Russian troops that were threatening the borders of Hitler's Third Reich.

In far Eastern Germany, an area that is now in Poland, about 10,000 Allied airmen, including Capt. Edward Bender of Cape Girardeau, were living on coarse black bread, meager rations of barley soup and the contents of Red Cross packages sent to prisoners of war. Life in Stalag Luft III at Sagan, now known as Zagan, was a routine of cold days and nights where news of Allied advances was passed by word of mouth from those lucky enough to catch a few moments of Western radio broadcasts on a clandestine set.

Then on the evening of Jan. 27, 1945, the prisoners were told they must leave the camp because the Germans did not want them to be liberated by the advancing Russians, who were driving toward the Oder River just days after liberating Warsaw.

Bender, like his fellow prisoners or "kriegies" — short for kriegsgefangenen — gathered up their belongings and were marched out of the camp into the bitterly cold countryside. They marched south and west, covering 35 miles in 27 hours with only brief rest periods and a four-hour stop in barns and stables.

Bender, now 90, recalls that he left the camp fairly well prepared for the journey. He had a backpack made from an old shirt, a couple of suits of long-johns, trousers, a blouse, an overcoat and a stocking cap. Supplies were being pulled on a makeshift sled. During the four-hour stop, prisoners took turns guarding the sled. But during Bender's turn, he left his watch to help a fellow prisoner and when he returned, the goods had been rifled by German civilian refugees and he saw his overcoat and Red Cross food parcel on the seat of a horse-drawn wagon.

There was nothing he could do, Bender recalled Friday in an interview in a room at his Cape Girardeau home where the walls tell the story of World War II air power and his personal mementos recall his part in the struggle. "A guard told me that if there was trouble with the civilians there would be one loser," he said.

Wartime chronicle

Bender, with the help of his wife of 57 years, Kay, and his daughters, Trinity Lutheran School principal Diane Maurer and Miriam Bender Larson of Knoxville, Tenn., has chronicled his wartime experiences in a book that is in the final stages of publication. Titled "Lest They Forget Freedom's Price: Memoirs of a World War II Bomber Pilot," the cover features Bender's photo and fingerprint from the official German document registering his POW status.

And to honor their father, Maurer and Larson next week will travel to Zagan for a re-enactment of the 50-mile march that took the kriegies to a railhead at Spremberg. They will join about a dozen other "Kriegie Kids," most far older than their fathers at the time of the march.

Maurer will explain her journey to her students this week in assemblies that Bender will attend, and post reports of the trek on the Internet.

"I am going for the experience, so I can put actual pictures to the stories I have heard over the years," Maurer said.

The re-enactors will endure some of the hardships their fathers encountered. Silesia in January is few people's idea of a vacation paradise. But stragglers won't be left beside the road, nights will be spent in hotels, not unheated barns, and there will be a heated motorcoach nearby with good food for those who are unable to march the entire route.

Maurer said she began walking as a training exercise in the summer and the recent cold weather has given her a taste of what to expect. She tries taking walks from the Lutheran School to her home near Cape Rock Drive at least daily. Some days, she said, she walks both ways.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Edward Bender worked for the Cape Girardeau Post Office at the corner of Broadway and Fountain Street when, on Dec. 7, 1941, the Japanese Imperial Navy attacked the U.S. Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor. He had tried to enlist in the Army Air Corps before the attack, because he expected to be drafted anyway.

But Army doctors had rejected him as a candidate to be an airman because of a slow heartbeat.

On Dec. 8, 1941, he told his supervisor that he planned to join the Navy and was walking upstairs at the post office building to the recruiting station when he saw a group of men in their skivvies being given physical examinations. Bender said he asked the doctor about the group and was told they were being screened for the Air Corps. He mentioned his slow heartbeat.

Told to run downstairs and back up again — there were 24 steps to the street — Bender's heart rate was 63 when he returned. "The doctor said 'that's all right,'" Bender recalled. "'Take off your clothes and get in line.'"

Ill-fated mission

By the end of January, Bender was in Arizona at Higley Field. Training continued over the next year at bases in California, Utah and Washington. Assigned to pilot B-17s, at the time the world's largest heavy bomber, Bender became an instructor. He trained five classes of new airmen before his assignment to England as part of the 457th Bomber Group.

On his 13th mission, he and the crew of 11 were forced to bail out over Normandy, France, when an engine caught fire as Bender switched fuel tanks. He came down in a training area teeming with young SS soldiers. Five of the crew found refuge with French resistance fighters and made their way back to England. Bender was reunited with his ball turret gunner and sent first to an interrogation center in Frankfurt, Germany, before being placed in the Sagan camp.

He arrived in April 1944, about a month after the mass breakout made famous in the 1963 film "The Great Escape."

Fuel for heat and cooking came from tree stumps pulled laboriously from the ground. The Germans provided them a hunk of bad black bread — prisoners joked harshly that it was mainly sawdust — and a half-cup of soup. With their Red Cross food parcels, the prisoners were "trying to feed 15 men on a half a can of corned beef and two or three bad potatoes," Bender said. "I went in weighing 160 pounds and came out weighing 114."

"Too cold to snow"

The weather during the forced march from Stalag Luft III is remembered as some of the coldest of the 20th century in that region. "I remember the guards said it was too cold to snow," Bender said.

At Muskau, two-thirds of the way through the march, Bender was housed in a pottery factory and glad to see the ovens were working. "It is the first time I had been warm for five days," he said.

For the final weeks of the war, Bender was sent first to a camp in Nuremberg, then transferred to Moosburg, where he was finally liberated by the U.S. Third Army commanded by Gen. George S. Patton.

Guards defending the camp surrendered when the Allies demanded, "OK,, Fritz, throw out your guns. For you, the war is over." Those words, familiar to every Allied prisoner but usually coming from a German, were music.

The thing he remembers most, Bender said, is the food he was given by his liberators. "It was an issue of British gray bread," he said. "It tasted wonderful."

Read more!

Interview in Bellevue Reporter prior to our trip.

Josh Hicks, a staff reporter for the Bellevue Reporter, in Bellevue, Washington, posted a short video of an interview he did with my dad and me a couple weeks before I flew to Europe to begin the "Road from Sagan".. Click here for a link to the full article.

Read more!

Sunday, February 15, 2009

The Dresden Bombing

We just watched the DVD of the mini series "Dresden," a joint venture by Koch Vision and the BBC. It's a very powerful story and has won awards for accuracy and cinematography. George recommended it and he provided some other information on the Dresden bombing, which occurred about two weeks after our fathers marched from SLIII to Spremberg. (Caution: there is one love scene in the hospital that parents may want to fast forward through, and the realistic portrayal of the death and destruction in the city may be too much for some children.) Read on to learn more details about Dresden from George...

Dresden was bombed on the night of February 13/14, by over 800 British Lancasters in two waves of attack, approximately three hours apart. The first wave dropped high explosives to blow holes in the roofs and walls of the buildings to expose the flamable inner wooden structures. The second wave dropped incindiaries to ignite the inner structures. The firestorm that resulted was 1,000 degrees centigrade with winds of 100mph. 90% of the city was destroyed, and the death toll was between 80,000 and 250,000. The actual number will never be known, as there were thousands of refugees in the city at the time.

The following afternoon, 1,300 B-17's from the 1st and 3rd air divisions of the U.S. 8th Air Force bombed the railway marshalling yards at Dresden with a mixture of high explosive bombs and incindiaries. Due to poor visibility from the smoke hanging over the city, the B-17's had to bomb by radar, and some of the bombs fell in the city center. A few days later, the 8th Air Force was supposed to bomb Chemnitz, but due to solid cloud cover, they were forced to bomb their alternate, which was Dresden. (Chemnitz was eventually bombed later.)

The Dresden bombing is significant to our fathers' stories because it both promised a quicker end to the war and contributed to the scarcity of food and provisions available for the German public and, therefore, to prisoners of the Third Reich. Read more!

Red Cross Parcels for the POWs

George Bruckert is a WWII reenactor who joined the "Kriegie Kids" on the march last month. George has interviewed many former POWs, and one of his friends, Lt. Jay Coberly, shared some information recently on the Red Cross parcels that came to the SLIII POWs. Read on for George's information from his interview with Jay...

Lt. Jay Coberly was a B-17 bombardier with the 94th Bomb Group, based at Bury St. Edmunds, England. He was shot down on October 14th, 1943, and was a prisoner in South Compound.

"Once a month they would give us one quarter of a Red Cross parcel. The soup was made out of cull potatoes the German GIs did not want. The bread was not as old as the kind we had to eat in the box car but certainly was not any where near fresh. The Red Cross parcels were piled high outside the main fence where we could see them, with more coming in each day, but they would only give us the quarter parcel."

Note: One full Red Cross parcel was a box about 3" deep and 12" square and contained the minimum amount of food required to sustain a man for one week at approximately 1700 calories per day. In an American box were small portions of spam, corned beef, powdered eggs, jelly or jam, powdered milk, soda crackers, dried raisins or prunes, powdered coffee, cigarettes, sugar, a chocolate "D" bar, salt and pepper. They also sometimes had tinned Salmon or Herring.

Read more!

Saturday, February 07, 2009

Side Trip to Lubin - One POW Left Behind

The January, 1944 burial of Lt. Sconiers. Gen. Clark is in the foreground on the right.

An hour away from Stalag Luft III is the small town of Lubin, Poland. Besides accompanying my fellow Kriegie Kids on the march and trip through Germany and Poland, I had one other “mission.” After some years of research, I became aware of one POW left behind. This POW was Lt. Ewart Sconiers, formerly of South Compound, where my own father had resided. Ewart has a fascinating, yet poignant, story. He washed out of pilot training during the war because he could not manage to land the big bombers. After he washed out, he became, like my father, a bombardier. On one of his missions, his co-pilot was killed and his pilot was very badly burned. Ewart was called up to the cockpit, and he soon realized that the only way the rest of the crew would be saved was if he took over and flew the crippled B-24 back across the English Channel and landed it. That is exactly what he did, landing at my father’s base at Horsham St. Faith. For that bravery, Ewart was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, and he also received a purple heart. FDR mentioned Ewart in one of his Fireside Chats.

On a later mission, Ewart’s plane was shot down, and he became a POW at Stalag Luft III. One day while walking on the icy circuit, he fell and hit his ear on a jagged tree stump. Infection set in, and because his ear problem was left untreated, he experienced more serious medical problems that eventually led to him displaying symptoms of mental illness. His fellow kriegies tried to protect him from the guards, but one day when the men were outside, the guards came into his barrack and took him away. The Germans, rather than repatriating him, removed him from the camp and sent him to a mental hospital in Lubin. The next day, Ewart was dead. Some Germans said he had a heart attack, and other Germans said he died of pneumonia. The kriegies did not believe either was the cause of his death.

On Jan. 29th,1944, a contingent of Senior American Officers, including then Col. A.P. Clark, “Padre Mac,” the well-loved Scottish chaplain, Col. “Rojo”Goodrich, and Lt. Stenstrom who had been on Sconiers’ crew, road on the train with their deceased friend to Lubin and buried him in a small cemetery there. The Germans encased his wooden casket in an elaborate metal covering that the SAOs carried to the cemetery. The wooden casket, which had been covered with an American flag, was then lowered into the ground. German wreaths adorned the grave but bore swastikas on the ribbons. The SAOs then sadly returned to Stalag Luft III.

The long evacuation march followed for the POWs of Stalag Luft III a year later, and soon they were liberated in Moosburg at Stalag VIIA. For 65 years, Lt. Gen. Clark has felt the pain of leaving Ewart behind. He drew me a map of what he remembered of that burial day, and I took it with me for the sake of comparison. Everything matched up as I walked the pathways to the cemetery that he and the other officers walked that day. Only recently have the wheels been set in motion by a team of researchers and friends to bring Ewart home.

For those few hours, on the 65th anniversary of Ewart’s burial, when I left my fellow Kriegie Kids and went to Lubin, I visited with those there that knew his story, including Mr. Stephen Marks, an American working in Lubin. His office is in the former mental hospital where Sconiers had been taken. Having recently become acquainted with Ewart’s niece, Pamela Whitelock, I represented her at the grave and memorial. I placed an American flag at the grave alongside a bouquet of purple irises. As I promised Pamela, I whispered to Ewart that she would come soon to bring him home. I was interviewed by the press in Lubin and before leaving the area, I took many pictures, some of which I will attach. A catalpa tree, with heart-shaped leaves, was planted at the gravesite by a “friend” of Ewart’s over 65 years ago. To this day, we still do not know who planted that tree.

When the Communists took over in that area of Poland immediately after the war, the U.S. was severely limited in its attempts to reclaim its fallen airmen. A team was allowed in in 1947, but it failed to find the grave. At one time, years later, Ewart’s sister went to Poland searching for her brother, but she could never find his grave. Not long ago, Mr. Stanisław Tokarczuk, a history teacher in Lubin, arranged for a memorial for Lt. Sconiers, and the people of Lubin have taken great interest in the bombardier’s story. Hopefully, updates will follow on the progress of his return to his native Florida where his niece has already arranged for a catalpa tree to be placed at his new burial site. And to his family’s delight and to the great relief of now 95-year-old Lt. General Clark, at the Air Force Academy, his fellow POW and friend will finally come home.

The pictures below illustrate the following:

1) Marilyn standing at Lt. Sconiers' gravesite.

2) The memorial for Sconiers, provided by the people of Lubin, Poland.

3) The former mental hospital where Sconiers was taken. It is now a Polish copper company.

4) Mr. Tokarczuk holds a pictures of Lt. Sconiers.

5) The chapel where Sconiers' body was held.

6) Pathway by the Memorial into the cemetary.

7) From the house in the distance, a German history teacher watched Sconiers' funeral in 1944.

8) Catalpa tree and lantern mark Sconiers' grave.

9) Large stork's nest on the way to Lubin, Poland. Storks migrate through Poland.

Read more!

Friday, February 06, 2009

Moosburger Zeitung Article - Translation

Here's a translation of an article concerning our trip, that appeared in the Moosburger Zeitung:

Click here to access a pdf of the German version of the article

Night marches in honor of their fathers Americans make a visit on the "Road to Sagan" and the ruins of Stalag VIIA in Moosburg.

They have flown thousands of miles in the heart of Europe's winter to finally make a 100 kilometer walk on foot : in the last ten days, children of former American prisoners of war followed the "Road to Sagan" in order to honor their fathers. At the end of World War II, the path they followed led from the Polish town of Sagan to the prisoner of war camp Stalag VIIA in Moosburg. Under the best care of Bernhard Kerscher, the Director of the Heimat-museum, they looked at, among other things, the remains of the former Wachbaracken in the Schlesierstrasse and also visited the memorial Oberreit. They call themselves "Kriegie Kids", and they have obviously listened intensely to the stories of their fathers, because the sons and daughters of former airmen Gore, Arnett, Bender, Burda, Keefe, Jeffers and Leary have a very good knowledge of past history. They had meticulously planned their trip on the "Road to Sagan”, which took them from the Polish city of Zagan, through the German towns of Spremberg, Dresden and Nuremberg, to their final destination in Moosburg.

It is there in Moosburg that, on April 29, 1945, their fathers lived one of the happiest moments of their lives – their deliverance from captivity. In January 1945, the Russian divisions had broken through the German defense lines and were rapidly advancing through Polish territory. Therefore the German Higher Command decided to evacuate Stalag Luft 3 in the Polish city of Sagan, so the 10,000 Allied airmen who were interned there wouldn’t be freed by the Russians.

Not in the least protected from the icy coldness of winter, hungry and freezing, the prisoners, in a long procession, walked in a westerly direction.

Some were put into Stalag XIIId after having reached Nuremberg, others, after a stop in Spremberg, made a 72-hour journey by truck to Stalag VII A in Moosburg. Nothing but misery awaited both groups in the utterly overcrowded camps. The trip for the "Kriegie Kids" was not that bad: Although they also marched 60 miles on foot through the Polish night, in order to experience, in the flesh, their fathers’ privations, at the end of their trek a bus was waiting for them to bring them back to their hotel. And while some wrapped themselves into authentic-looking "Aleutian Coats” or in khaki-colored blankets, others, especially the older ones, preferred thick boots and down coats. The cold didn’t diminish in any way the enthusiasm with which they wanted to honor their fathers.

The arrival in Moosburg was a little hectic: due to an error in communication the group had been announced for Tuesday. Fortunately, however, Bernhard Kerscher, Head of the Heimat-museum, was on the spot to greet the visitors when they knocked on the door on Monday morning. A translator was quickly found in the person of the newspaper “Moosburger Zeitung”’s Editorial Manager Karin Alt, who managed to give an answer to (almost) all the questions.

As Mr Kerscher was just a boy when the Americans liberated the camp, some questions couldn’t find a satisfactory answer, for example, from which side did the first American "tank" reach the Camp? That’s why Bernhard Kerscher told them a lot about his own recollections, things the guests had never heard before. The Americans in turn, reported how much their fathers had suffered from hunger and how disgusting were the six-legged nightly "co-habitants” in their sleeping quarters. How they shivered in the too desperately small latrines, where they had been advised to refrain from smoking, because any small spark in the gaseous atmosphere could have provoked an explosion.

It was with great joy that the visitors accepted the Stalag brochures and the beer mugs distributed by Mr Kerscher – souvenirs for the surviving fathers of participants, all in their eighties and nineties now. After a short lunch break, the group went to the Neustadt (New Town) part of the city, along the railroad tracks, towards a large wooden watchtower leading to the entrance of the former Camp. Along the present-day Sudeten-landstraße – the wartime Hauptstrasse, which divided the camp in two – they reached the Schlesierstraße. Here, of course, many photographs were taken of the three still standing “Wachbaracken”, the former watchtowers (”Goon boxes“), while some piece of brick or a pinch of dust were picked as a souvenir to take home. The American guests learned that the City Council is building a Stalag Museum, and that in future a renovation of the last wartime barracks will be undertaken. Some visitors were also amazed at how the New City had changed - many were not for the first time here. They told of an unforgettable stay at Martin Braun’s. He has made a lasting impression on the "Amis“ (Americans) with his warm cordiality, his hospitality and also with his skills in the art of magic.

Just a quick, short stop to visit the Memorial Fountain, in its winterly silence, before the tour ended with a visit to the memorial Oberreit. Eleven Americans had been buried in the former Stalag Cemetery, but soon after the war their remains had been brought to their homeland. The “Kriegie Kids” took leave of Moosburg with heartfelt thanks for the friendly reception in the city.

Read more!

Click here to access a pdf of the German version of the article

Night marches in honor of their fathers Americans make a visit on the "Road to Sagan" and the ruins of Stalag VIIA in Moosburg.

They have flown thousands of miles in the heart of Europe's winter to finally make a 100 kilometer walk on foot : in the last ten days, children of former American prisoners of war followed the "Road to Sagan" in order to honor their fathers. At the end of World War II, the path they followed led from the Polish town of Sagan to the prisoner of war camp Stalag VIIA in Moosburg. Under the best care of Bernhard Kerscher, the Director of the Heimat-museum, they looked at, among other things, the remains of the former Wachbaracken in the Schlesierstrasse and also visited the memorial Oberreit. They call themselves "Kriegie Kids", and they have obviously listened intensely to the stories of their fathers, because the sons and daughters of former airmen Gore, Arnett, Bender, Burda, Keefe, Jeffers and Leary have a very good knowledge of past history. They had meticulously planned their trip on the "Road to Sagan”, which took them from the Polish city of Zagan, through the German towns of Spremberg, Dresden and Nuremberg, to their final destination in Moosburg.

It is there in Moosburg that, on April 29, 1945, their fathers lived one of the happiest moments of their lives – their deliverance from captivity. In January 1945, the Russian divisions had broken through the German defense lines and were rapidly advancing through Polish territory. Therefore the German Higher Command decided to evacuate Stalag Luft 3 in the Polish city of Sagan, so the 10,000 Allied airmen who were interned there wouldn’t be freed by the Russians.

Not in the least protected from the icy coldness of winter, hungry and freezing, the prisoners, in a long procession, walked in a westerly direction.

Some were put into Stalag XIIId after having reached Nuremberg, others, after a stop in Spremberg, made a 72-hour journey by truck to Stalag VII A in Moosburg. Nothing but misery awaited both groups in the utterly overcrowded camps. The trip for the "Kriegie Kids" was not that bad: Although they also marched 60 miles on foot through the Polish night, in order to experience, in the flesh, their fathers’ privations, at the end of their trek a bus was waiting for them to bring them back to their hotel. And while some wrapped themselves into authentic-looking "Aleutian Coats” or in khaki-colored blankets, others, especially the older ones, preferred thick boots and down coats. The cold didn’t diminish in any way the enthusiasm with which they wanted to honor their fathers.

The arrival in Moosburg was a little hectic: due to an error in communication the group had been announced for Tuesday. Fortunately, however, Bernhard Kerscher, Head of the Heimat-museum, was on the spot to greet the visitors when they knocked on the door on Monday morning. A translator was quickly found in the person of the newspaper “Moosburger Zeitung”’s Editorial Manager Karin Alt, who managed to give an answer to (almost) all the questions.

As Mr Kerscher was just a boy when the Americans liberated the camp, some questions couldn’t find a satisfactory answer, for example, from which side did the first American "tank" reach the Camp? That’s why Bernhard Kerscher told them a lot about his own recollections, things the guests had never heard before. The Americans in turn, reported how much their fathers had suffered from hunger and how disgusting were the six-legged nightly "co-habitants” in their sleeping quarters. How they shivered in the too desperately small latrines, where they had been advised to refrain from smoking, because any small spark in the gaseous atmosphere could have provoked an explosion.

It was with great joy that the visitors accepted the Stalag brochures and the beer mugs distributed by Mr Kerscher – souvenirs for the surviving fathers of participants, all in their eighties and nineties now. After a short lunch break, the group went to the Neustadt (New Town) part of the city, along the railroad tracks, towards a large wooden watchtower leading to the entrance of the former Camp. Along the present-day Sudeten-landstraße – the wartime Hauptstrasse, which divided the camp in two – they reached the Schlesierstraße. Here, of course, many photographs were taken of the three still standing “Wachbaracken”, the former watchtowers (”Goon boxes“), while some piece of brick or a pinch of dust were picked as a souvenir to take home. The American guests learned that the City Council is building a Stalag Museum, and that in future a renovation of the last wartime barracks will be undertaken. Some visitors were also amazed at how the New City had changed - many were not for the first time here. They told of an unforgettable stay at Martin Braun’s. He has made a lasting impression on the "Amis“ (Americans) with his warm cordiality, his hospitality and also with his skills in the art of magic.

Just a quick, short stop to visit the Memorial Fountain, in its winterly silence, before the tour ended with a visit to the memorial Oberreit. Eleven Americans had been buried in the former Stalag Cemetery, but soon after the war their remains had been brought to their homeland. The “Kriegie Kids” took leave of Moosburg with heartfelt thanks for the friendly reception in the city.

Read more!

Wednesday, February 04, 2009

Moosburg to Journey's End

On Monday, we arrived in Moosburg to find that the museum director and news reporters were expecting us on Tuesday. Fortunately, Karin Alt, one of the reporters, showed up and kindly translated for the director, Mr. Kerscher. Mr. Kerscher had been a young boy during the war and he still had vivid memories of Stalag VII-A and Patton's liberation of the camp. In the following video, he shared some information on the Red Cross parcels that were delivered to the prisoners.

Moosburg was a quaint little town with a beautiful church (see pictures) that is in very good shape. We all shopped at an open-air market after touring the church and then moved on to see the museum. Mr. Kerscher kindly gave each family that represented a POW held at Moosburg, a commemorative mug, and a book and copied handout on the camp. The museum, though small, is quite good with wonderful artifacts from Moosburg's early history and quite a bit from Stalag 7-A. They even had one of the wooden ships made by the Kriegies and one of the clandestine radios.

After touring the museum, we rode the bus out to the area where Stalag 7-A was located. There are still three barracks remaining, but sadly, they are destined to be torn down later this year. I wish there were funds available to restore one of them! They are stucko'd buildings with the original shutters, which have since been painted in bright colors. The area is low-income housing and the barracks house several apartments. A few of us entered to take pictures down the hall but were quickly ushered out by the translator who cautioned us to respect the residents' privacy (whoops!).

We said our good-byes to Mr. Kerscher and Karin Alt and drove on to Munich, tired but feeling that we had closure for the experience. Mr. Kerscher had described horrendous conditions at the camp in the last few months, with gross over-crowding. My father had arrived there just four days prior to Patton's liberation and he described being in the last tent and having only a shoe's-width between the men's bed rolls. I thank God that he didn't have to endure the situation long. In his memoirs, he is quick to describe the indomitable spirit of the Kriegies. He described a trip to the latrines where he saw the sign:

"Please do not throw cigarette butts into the latrines - it renders them almost un-smokable!"

After visiting the barracks site at Moosburg, we drove on to Munich for the last night of our trip. We had a German dinner and turned in, warn-out and ready for an early flight home the next morning.

We have made friends that we'll keep for life. We've walked (100 kilometers!) in our fathers' footsteps and seen the places they saw. We will never know the hardships they endured, but we have a greater appreciation for what they endured. To explain the motivation of our fathers, my father ended his memoirs with the following, quite appropriate quote from the 13th century Dominican friar, philosopher and theologian St. Thomas Aquinas:

"Those who wage war justly aim at peace... we go to war that we may have peace."

See updated pictures at: Forced March Trip Pictures

Read more!

Moosburg was a quaint little town with a beautiful church (see pictures) that is in very good shape. We all shopped at an open-air market after touring the church and then moved on to see the museum. Mr. Kerscher kindly gave each family that represented a POW held at Moosburg, a commemorative mug, and a book and copied handout on the camp. The museum, though small, is quite good with wonderful artifacts from Moosburg's early history and quite a bit from Stalag 7-A. They even had one of the wooden ships made by the Kriegies and one of the clandestine radios.

After touring the museum, we rode the bus out to the area where Stalag 7-A was located. There are still three barracks remaining, but sadly, they are destined to be torn down later this year. I wish there were funds available to restore one of them! They are stucko'd buildings with the original shutters, which have since been painted in bright colors. The area is low-income housing and the barracks house several apartments. A few of us entered to take pictures down the hall but were quickly ushered out by the translator who cautioned us to respect the residents' privacy (whoops!).

We said our good-byes to Mr. Kerscher and Karin Alt and drove on to Munich, tired but feeling that we had closure for the experience. Mr. Kerscher had described horrendous conditions at the camp in the last few months, with gross over-crowding. My father had arrived there just four days prior to Patton's liberation and he described being in the last tent and having only a shoe's-width between the men's bed rolls. I thank God that he didn't have to endure the situation long. In his memoirs, he is quick to describe the indomitable spirit of the Kriegies. He described a trip to the latrines where he saw the sign:

"Please do not throw cigarette butts into the latrines - it renders them almost un-smokable!"

After visiting the barracks site at Moosburg, we drove on to Munich for the last night of our trip. We had a German dinner and turned in, warn-out and ready for an early flight home the next morning.

We have made friends that we'll keep for life. We've walked (100 kilometers!) in our fathers' footsteps and seen the places they saw. We will never know the hardships they endured, but we have a greater appreciation for what they endured. To explain the motivation of our fathers, my father ended his memoirs with the following, quite appropriate quote from the 13th century Dominican friar, philosopher and theologian St. Thomas Aquinas:

"Those who wage war justly aim at peace... we go to war that we may have peace."

See updated pictures at: Forced March Trip Pictures

Read more!

From Spremberg to Moosburg

As I sit here recouping from jet lag, enjoying my morning coffee and bread with Johannesbeeren jam that I brought back from Germany, I will try to recapture the memories of the last days of our trip.

As I sit here recouping from jet lag, enjoying my morning coffee and bread with Johannesbeeren jam that I brought back from Germany, I will try to recapture the memories of the last days of our trip.After leaving Spremberg on Saturday, we drove to Dresden. Hans had described the devistation, and while driving there, George pulled out a DVD for us to watch: "Dresden: An Epic Mini-Series" (2008). This is a very accurate collaborative production by the German Koch Vision and the BBC, that presents a fictional character's account of the bombings of the city and of London. Extras on the DVD include actual archival footage of the bombings that illustrate the amazing scope of the destruction to both Dresden and London. Prior to the war, Dresden was called the art capital of the world and it is once again a beautiful city, although residents report that it is nothing like it once was. Once in Dresden, we climbed to the top of the recently restored Lutheran Frauen Kirche to see a fantastic, open-air view of the city. We purchased brats and Dresden stollen (fruitcake) which was good, but not as good as my Grossmama's (Grandmother's), and we took pictures of the statue of Martin Luther in the square.

See pictures of the trip and

Read more about our trip to Nuremberg.

Later that day, we drove to Nuremberg. (You'll note on maps that the Germans spell the city name as Nurnberg, with an "umlaut" - two little dots - over the "u") Nuremberg is known as a city "of wit," where inventiveness and curiosity are fostered. Diane and I found miniature silver "funnels" at the information center that represent funneling knowledge into the bearer. That night and the next we stayed in a 700 year old hotel within the scenic walls of the Old City, - it was really quaint, comfortable, and had a great breakfast. (The Elch - The Elk)

Sunday morning Becky, Diane and I got up early and attended church at St. Lorenz. We hurried through the bitter cold on quiet cobblestone streets to arrive slightly late. This wouldn't have been a problem except that the small, early service was held in a tiny side chapel that had only three rows of pews. (I felt like I was upholding the family tradition when our tardiness meant that we had to sit in the front row.) The pastor spoke on the Transfiguration of Jesus (Matthew 17:1-7), and I caught bits of his message to share with the others. He emphasized that while we often have "mountaintop experiences" in life, it is important to remember that God is with us in the valleys, too.

I am sure that my father was aware of God's presence during his days at Stalag 13-D. He shared that there was a rail marshalling yard very close to their barracks there, and that they could hear the Allied bombs whistle close overhead. After several close calls, he and his fellow Kriegies began to dig trenches with tin cans from their Red Cross parcels. At first, the German guards stopped them, but then one brought four shovels and they were allowed to continue. The reason became clear when the Kriegies ran out to the trenches during the next raid, only to find that the guards had jumped into the trenches ahead of them. They enlarged the trenches the next day.